Embracing Your Sphere of Influence: A Behavior Analyst’s Guide to Transforming Society Through Applied Behavior Analysis

My Missing Piece in ‘Saving the World with Behavior Analysis’

I'm sure you've heard the phrase "Saving the World with Behavior Analysis" countless times—I definitely have. Early in my career, this slogan deeply resonated with me, sometimes as an empowering statement reflecting confidence in our skills to solve big societal problems, and other times as a hopeful, almost idealistic affirmation of our field’s potential. Heward et al. (2022) have thoroughly documented just how broad our application of science has become—350 unique applications. Historically, this phrase emerged during the Vietnam War and the American counter-culture era, when behavior analysts took on ambitious social justice issues—civil rights, economic equality, and environmentalism—by collaborating to apply behavior analysis in practical, meaningful ways.

Over time, though, I've started to question whether our field still shares that unified vision. In the early days, behavior analysts tackled massive societal challenges, from developing instructional systems for NASA to reshaping juvenile justice programs. More recently, our success—and funding—has predominantly focused on services for neurodiverse populations, especially autism support. While undeniably vital, even this work now faces increased scrutiny, both externally from critics questioning our methods and internally from those reconsidering our ethical priorities. This tension became particularly evident in my own career when I found myself co-managing a program that supported 120 adults with disabilities, employing 55 staff members on an annual budget of $1.3 million. Although this budget initially seemed substantial, reality quickly set in: most employees earned just above minimum wage, fixed costs and overhead expenses piled up, and legislatively set rates necessitated coordination and lobbying efforts beyond our financial means. Suddenly, even simple decisions—such as purchasing a ~$5 reinforcer—became impossible, forcing me to reconsider the bold claim that behavior analysis alone could "save the world."

This experience—and others like it—highlighted an unexpected gap in my training. Although my education was thorough, covering areas well beyond current standards, such as behavioral pharmacology, neuroscience, and organizational behavior management, it didn't fully equip me to navigate the practical realities of finance and administration. This isn't a critique of my educators, who provided an outstanding foundation, but rather a reflection on the complexity of real-world challenges we encounter daily.

If we're truly committed to "saving the world," perhaps it's time our field embraces substantial interdisciplinary training, equipping behavior analysts with practical tools to achieve sustainable impacts beyond theory alone. I'm not alone in this realization; it's common among practitioners once they step beyond graduate training to come to this realization. Indeed, many professional organizations within our field feverishly work to align toward this vision (e.g., BACB, CASP, ABAI, APBA). My intention here is not to critique these organizations but rather to provide a framework for individual practitioners navigating their personal and professional lives.

The Sphere of Influence

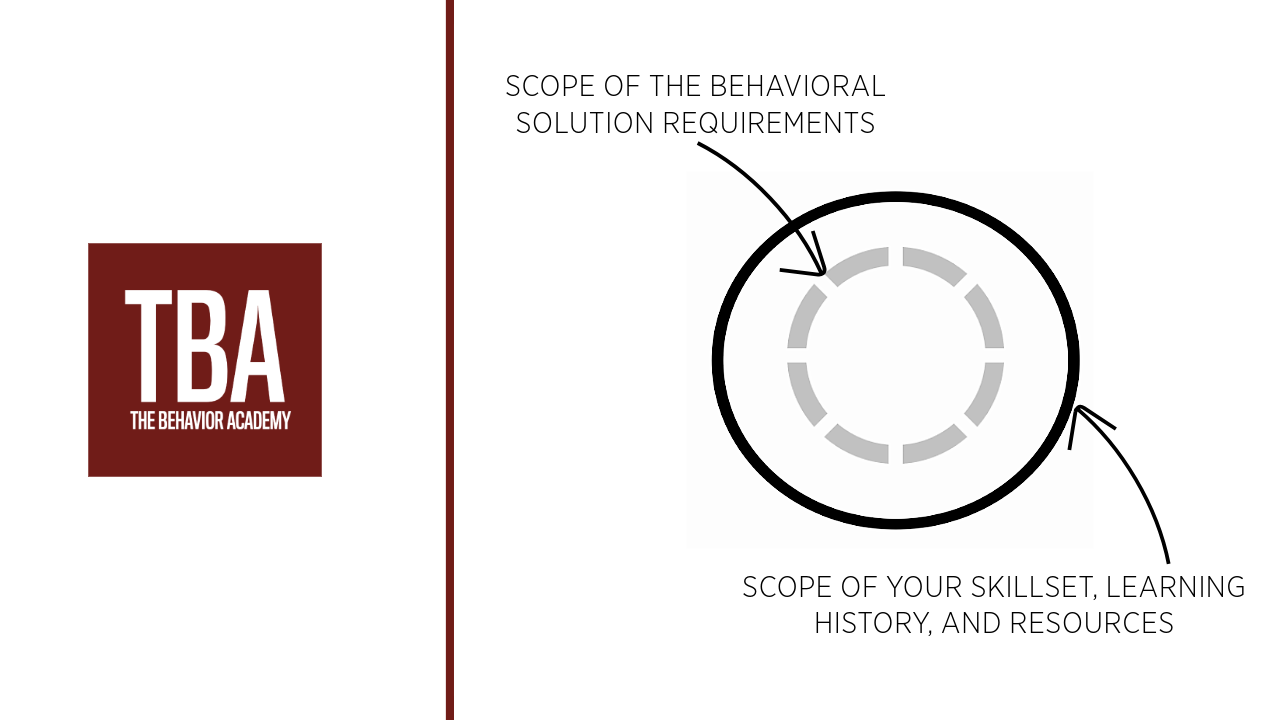

For many, the idea of "saving the world with behavior analysis" evolves or wanes over time due to personal and professional pressures. For those who persist, it becomes more nuanced, shaped by encounters with complex real-world scenarios. Central to this evolution is what I call the concept of one's "Sphere of Influence," defined by an individual's unique blend of skill set, learning history, and available resources. Your Sphere of Influence represents the boundary within which your actions can effectively induce change. Recognizing this helps behavior analysts better understand their strengths and limitations, prompting meaningful engagement with other disciplines to broaden their impact. The example below illustrates a scenario in which one's scope of influence surpasses the necessary conditions to foster prosocial change.

Depending on the situation presented to you, these metaphorical spheres change. In the situation below, one's sphere of influence can barely meet the present requirements.

Of course, these limits can be pushed well beyond a behavior analyst's current skill set, learning history, and resource availability in which failure is inevitable (the degree to which it is realized and the non-linear effects of this failure depends on each unique situation).

While a "Sphere of Influence," isn't rooted within the behavior analytic literature, it has served as an extremely useful tool for navigating my personal life and professional career. I believe there are two profoundly valuable implications for behavior analysts to consider if they leverage this concept:

- It is the right of any behavior analyst to accept or systematically alter their Sphere of Influence to meet the needs of their role in society.

- It is the duty of the individual behavior analyst and their close colleagues to ensure that the perception of their Sphere of Influence is an accurate reflection of the reality of their Sphere of Influence.

Scope of Competence and Its Role in the Sphere of Influence

Within behavior analysis, the term scope of competence refers to the boundaries of what a practitioner is qualified to do based on their formal education, supervised experience, and ongoing professional development. The Behavior Analyst Certification Board (BACB) emphasizes this principle as a central ethical mandate: practitioners must only provide services in areas where they have demonstrated competence. For example, a behavior analyst trained in early intervention for children with autism is not inherently qualified to design organizational systems in corporate environments or to deliver clinical services in neuropsychology without additional training and oversight. The concept is meant to protect clients and maintain the integrity of the science, ensuring that interventions are both effective and ethically delivered.

However, scope of competence is only one element of a larger system that determines our real-world effectiveness. While it draws a line around what we should do professionally, it doesn’t account for the broader environmental and systemic variables that shape our capacity to create meaningful change. This is where the concept of a Sphere of Influence becomes critical. A person might be highly competent in a given area but still lack the authority, social capital, funding, or collaborative partnerships necessary to translate their expertise into impact. Conversely, someone might find themselves with a large platform or resource base, but without the competence needed to act responsibly within it. Understanding your Sphere of Influence involves integrating—not just your competencies—but also your history, context, and available leverage points. It’s a more nuanced, dynamic model of action that reflects the complex contingencies we operate under.

In this way, scope of competence is necessary but insufficient on its own—it provides ethical guardrails, but not a roadmap for influence. By contrast, your Sphere of Influence invites a more comprehensive self-assessment: what do you know, what can you do, what resources do you control, and who can you collaborate with to extend your reach responsibly? Framing your work through this lens enables more honest, pragmatic planning—and positions you to seek out the multidisciplinary knowledge and partnerships required for large-scale change. The path to "saving the world with behavior analysis" does not lie in isolated mastery, but in expanding your Sphere of Influence while remaining anchored in ethical competence. It’s the intersection of both that offers the most significant promise.

Behavior Analysis + "_____"

Early in my career, I passionately believed behavior analysis alone could save the world. But over time, this evolved into what I now call "Behavior Analysis +," the idea that behavior analysis combined intentionally with other fields is far more powerful. Again, this isn't something I've uniquely discovered, and many of my past mentors have instilled this thinking. In fact, it's present in much of our literature. This is clearly present in what Zing Yang Kuo (1967) described as "epigenetic behaviorism," which acknowledges the biological limits to behavioral change. If you promise me a reward every time I pick up my arms and fly off a stage, no amount of shaping or reinforcement will make it happen—I don't have the biological structures to do it. This simple example underscores why integrating biological and morphological knowledge is crucial: understanding our biological limits can make us more effective behavior analysts.

Biology isn't just theoretical—it's practical. I've learned firsthand that ignoring biology and morphology creates barriers. For instance, shaping vocal approximations in someone who physically can't produce certain sounds is ineffective, no matter how precise your behavioral techniques are. Collaborating closely with speech therapists, I've realized that behavior analysis alone doesn't always hold the solution. Our effectiveness increases significantly when we embrace knowledge from related fields, recognizing biological constraints and adapting our approaches accordingly.

Another field I've increasingly turned toward is economics, initially motivated by my own experience managing student debt and self-employment without the safety net of employer-sponsored retirement. However, exploring economics has revealed to me the profound role financial incentives, government policy, and personal economic decision-making play in human behavior. Understanding these elements is critical whether you're setting wages for staff or deciding between branded or off-brand purchases. Economics isn't just personal finance—it's understanding how larger economic structures shape daily behavior.

It appears that embracing this "Behavior Analysis +" perspective is essential if we genuinely aim to create lasting, meaningful change. By broadening our view beyond traditional training, we can understand the limits of our methods, become more effective collaborators with experts in other fields, and position ourselves to make tangible impacts in diverse real-world situations. It's clear to me now that the future of our field doesn't just lie in refining our current approaches but in intentionally integrating our expertise with other disciplines and creating innovative solutions to the complex challenges we all face.

So, while one could conceivably include any other discipline or school of thought into the "Behavior Analysis +" framework, I have been feverishly studying the intersection of two in particular that I wish to share.

Behavior Analysis + Economics

Traditionally defined economics is the social science that explores how societies manage the production, distribution, and consumption of goods and services. It involves studying how individuals, businesses, governments, and nations make decisions about allocating resources to maximize efficiency and satisfy their wants and needs. Translating this into behavior analytic language, economics can be seen as the study of how organisms allocate their limited behavior and resources among competing contingencies of reinforcement—think of the Matching Law, which illustrates choices based on reinforcement schedules and rates.

B.F. Skinner, a foundational figure in behavior analysis, deeply integrated economic concepts into radical behaviorism. Operant conditioning itself embodies economic principles, as organisms allocate responses based on consequences, mirroring economic decision-making based on expected outcomes. Skinner's insights also paved the way for behavioral economics, an interdisciplinary field blending psychology and economics, focusing on phenomena like delay discounting and response allocation. Skinner viewed reinforcers analogously to economic utilities, emphasizing that organisms aim to maximize reinforcement much like economic agents strive to maximize utility. (See "Hacking Your Life with Behavior Analysis" by Derek Reed here on The Behavior Academy for a primer on Behavioral Economics)

Further, Skinner's examination of choice behavior aligns closely with economic theories of decision-making. His research on schedules of reinforcement reveals how organisms make choices based on the relative magnitude and timing of reinforcers, reflecting economic decision-making processes. His work on concurrent schedules similarly demonstrates principles of resource allocation, showing how organisms distribute their behaviors in environments offering varying reinforcement opportunities, directly paralleling economic principles.

While a full analysis of different economic systems is beyond the scope of this blog, we can explore how Skinner’s findings help explain how economic contingencies shape patterns of behavior that contribute to both individual behavior and cultural practices. The United States exemplifies a mixed economy, blending capitalism and governmental oversight. Capitalism in the U.S. involves predominantly private ownership and market-driven decision-making based on supply and demand. Government intervention supplements this through regulations protecting consumers, ensuring fair competition, and providing critical public services like education, healthcare, transportation, and national defense. Welfare programs provide social safety nets supporting individuals and families in need.

As behavior analysts, understanding economics is more than theoretical—it's a pathway to recognizing broader societal influences on behavior. Elements of our mixed economy, such as regulatory agencies (e.g., Environmental Protection Agency, Department of Health and Human Services, Food, and Drug Administration), social programs (e.g., Social Security, Medicare and Medicaid, Unemployment Insurance), and monetary policies through Government Spending and the Federal Reserve, profoundly shape the daily contingencies we experience. Economic contingencies are inescapable for nearly everyone, continuously shaping behavior by influencing access to necessities, opportunities, and reinforcers in unique ways for both ourselves and those we serve. Even those with immense wealth are not entirely free from these influences, as economic contingencies continue to shape the broader environment in which decisions are made. Daily choices—what to buy, where to live, how to work—are all guided by the contingencies imposed by the economic system, regardless of one's resources. There are just more degrees of freedom that they experience in the choices available to them.

Behavior Analysis + Game Theory

Game Theory is an economics and behavioral science framework that helps us understand cooperation and defection through structured models. Perhaps the best-known example is the Prisoner’s Dilemma, which vividly demonstrates how individually optimal decisions can collectively lead to worse outcomes. Cooperation involves two or more organisms coordinating their behaviors, resulting in mutually reinforcing consequences. Defection, on the other hand, occurs when a player chooses not to cooperate with others, opting instead for a strategy that benefits themselves at the expense of the group. In short, although cooperation would yield the best overall result, each prisoner typically chooses to defect out of self-interest, ultimately harming both.

Think about the Prisoner’s Dilemma in a business context. Two competing companies can choose to set prices either high (cooperation) or low (defection). If both cooperate and keep prices high, they both benefit. However, if one defects and lowers prices, it captures a greater market share, harming the other company. If both defect and lower prices, they engage in a price war, and both suffer. We've all seen versions of this in our own industry—for instance, when competing for CEUs or battling for market positioning. It illustrates the complexity and importance of understanding when and how cooperation can actually lead to greater long-term success.

Interestingly, my exploration of Game Theory and Behavior Analysis also led me into another related arena: social media and the hidden mechanics of digital algorithms. Since around 2015, I haven't practiced traditional behavior analysis directly with clients. Instead, I've been diving deep into understanding how social media algorithms influence human behavior—particularly, how defectors (those prioritizing self-interest over collective good) often gain an economic edge online. Through intensive personal study, specialized training, and professional conferences, I've seen firsthand how these algorithms incentivize defection-like behaviors: clicks, views, and attention at almost any cost. (For those interested in diving further into this, see Social Media and Behavior Analysis: Leveraging Social Media to Expand Your Impact a dedicated course including BACB CEUs)

When Defection Scales: The Data Economy Behind Big Tech

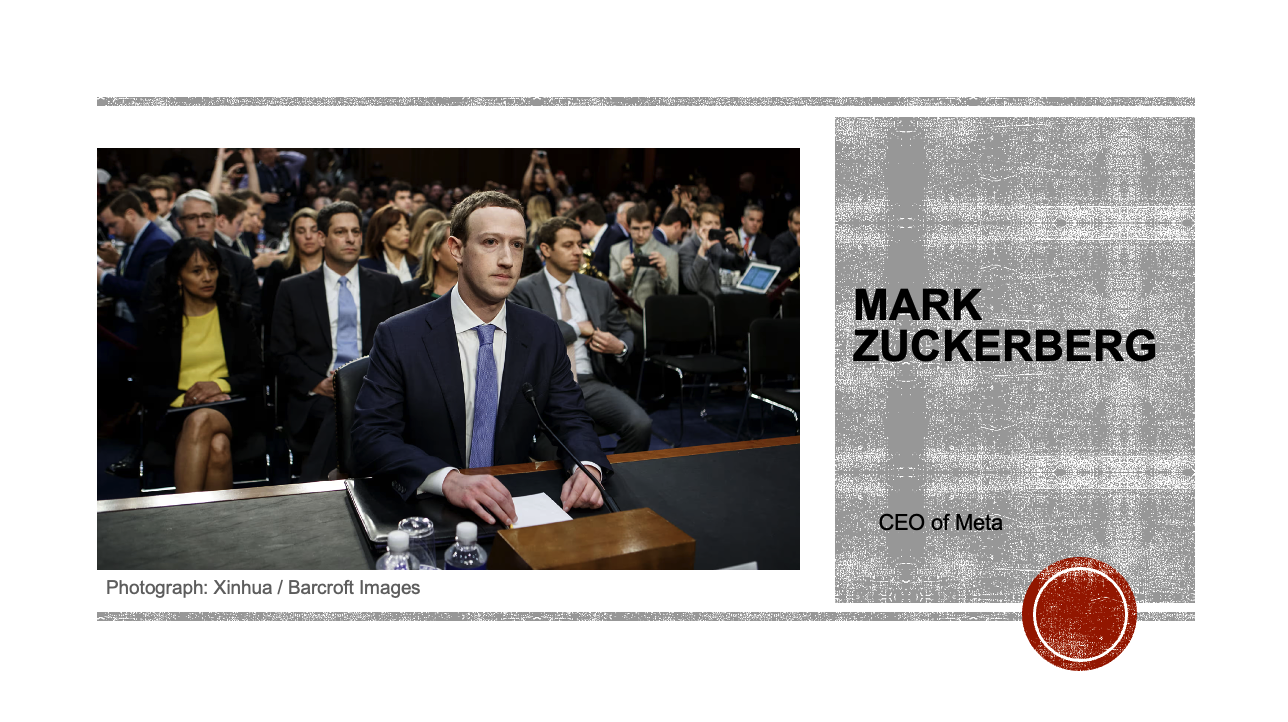

Let's talk about Facebook—and specifically, Mark Zuckerberg—to explore a powerful example of cooperation versus defection. Back in 2003, Zuckerberg famously created FaceMash by hacking Harvard’s database, allowing fellow students to rate peers as "Hot or Not." Around this time, he was also collaborating—or so they thought—with the Winklevoss twins on a social networking project called HarvardConnect. Instead of continuing that collaboration, Zuckerberg launched his own site, initially known as "The Facebook," eventually opening it to the public as simply "Facebook." Later, Zuckerberg settled a lawsuit with the Winklevoss twins for $65 million, an amount that, compared to Facebook's current trillion-dollar valuation, might simply be considered a cost of doing business. In this scenario, defection—the choice to prioritize individual success over cooperation—paid off massively.

This situation perfectly illustrates a modern version of the Prisoner’s Dilemma. Zuckerberg could have cooperated by sticking with HarvardConnect, but he chose defection by developing his own competing platform. The Winklevoss twins initially trusted Zuckerberg (cooperated), only choosing defection later through legal action when their trust was broken. Although the twins eventually settled for $65 million, this payout was trivial compared to Facebook’s eventual trillion-dollar valuation, illustrating how defectors, especially in technology, often succeed economically. The uncomfortable truth here is that defection can be highly profitable—often far more profitable than cooperation.

Facebook's success isn't only built on defection at its founding; its entire economic model thrives on user-generated content and behavioral data monetization. Every day, nearly half of the world interacts with Facebook-owned platforms, unknowingly generating immense amounts of data. This data is harvested and sold to advertisers, creating a cycle where the platform profits immensely from user behavior. You've likely heard the saying, "If you're not paying for the product, you are the product." Platforms like Facebook, Instagram, Snapchat, Threads, TikTok, X (formerly Twitter), and YouTube exemplify this model. In fact, it's become so pervasive it's now standard across nearly every digital industry.

Cambridge Analytica was a data analytics company that harvested millions of Facebook users' data through an app exploiting loopholes in Facebook's platform policies. They collected not only user data but also data from users' friends, creating detailed psychographic profiles that enabled highly targeted political advertising. Their tactics significantly influenced major global events, including the 2016 U.S. Presidential Election and the Brexit referendum.

When I started understanding how deeply embedded these defection-based models were in social media, I reconsidered my own relationship with these platforms. It became clear that defection—prioritizing individual or corporate gain at the expense of others—was often a reliable economic strategy, at least in the short term. But is this approach sustainable or desirable long-term? As behavior analysts and consumers, it's crucial we recognize these dynamics. Cooperation might seem less lucrative initially, but fostering genuine collaboration—both within our field and more broadly—could lead to outcomes that are ultimately healthier, more ethical, and genuinely aligned with our shared values.

Defection Isn't Just a Tech Problem—It's In "Applied Behavior Analysis"

But defection isn't limited to tech giants—it impacts our field, too. Imagine a network of providers serving children with disabilities: cooperating would mean sharing resources, expertise, and training to collectively improve outcomes. Yet, some organizations choose defection, keeping their innovations secret to secure competitive advantages. Initially, these defectors may thrive, attracting more clients through their perceived unique methods. However, the long-term consequences can be severe: cooperation deteriorates, trust fades, and ultimately, children miss out on advancements that collaborative approaches might have provided. Understanding the dynamics of cooperation and defection is critical if we aim to build sustainable solutions—both within behavior analysis and in society as a whole.

Despite the promise of the Behavior Analysis + model, integrating our science with other disciplines, a deeper dive into game theory exposed a fundamental flaw: cooperation, while ideal in theory, often fails in practice due to the consistent success of defectors. Especially in economically driven systems, defection tends to be the more immediately reinforced choice, creating a pattern where individual gain outweighs collective progress.

This realization didn’t just challenge the feasibility of interdisciplinary solutions—it called into question the very strategies we rely on to effect change. Observing this repeatedly can lead to deep frustration, even despair. I found myself cycling through different models of understanding behavior and human interaction, searching for something that made sense. After seeing this cycle enough times, it’s easy to fall into apathy, believing nothing truly works or matters—a state that many of us in behavior analysis have encountered at some point. Some colleagues of mine have never emerged from this phase of disillusionment, losing faith entirely in the ability to "save the world with behavior analysis." But then I had a realization: defection isn't about inherent morality or personality flaws—circumstances shape it. Behavior analysts know better than anyone that environment determines behavior. When an organization chooses self-interest over cooperation, it usually responds optimally to pressures like resource scarcity, competitive pressures, or past experiences. Take, for example, a scenario in which two therapy organizations serve children with disabilities. If one organization defects from cooperation—by withholding resources or specialized methods—it often does so believing it will gain a competitive advantage, more funding, or more clients. They're not necessarily malicious; they're simply acting based on their circumstances and experiences. (For more on this circumstantial view, see "This Way of Thinking" by Patrick C. Friman here on The Behavior Academy)

Yet, when viewed through the lens of Game Theory, this pattern becomes alarmingly predictable. Mutual cooperation yields the greatest overall benefits—shared growth, stability, and improved outcomes. However, if one organization defects, it often secures a short-term advantage—until the other follows suit. The result is a downward spiral of mistrust and diminished effectiveness. We’ve seen this unfold repeatedly within our own field, such as when new professional organizations emerged in response to perceived failures of existing institutions. Our history is full of moments where defection was not only common but seemingly necessary to provoke change or carve out new directions, highlighting persistent tensions between collaboration and autonomy.

Recognizing defection as a product of environment—not character—offers a meaningful path forward. It’s easy to become cynical when defection so often leads to immediate rewards. But if we examine the contingencies maintaining this pattern, we can design systems that tip the scales back toward cooperation. By identifying and adjusting the variables that reinforce self-interested behavior, we make it more likely that practitioners, organizations, and institutions will opt into shared success over isolated wins.

Cooperation is not automatic—it must be cultivated intentionally through environmental design and systemic change. People and organizations behave in accordance with the contingencies surrounding them. Instead of blaming defectors, we need to ask: what reinforcement systems made this the optimal choice? If we want collaboration to thrive, we must actively engineer the conditions that make it desirable, sustainable, and mutually reinforcing. With that in mind, before introducing a different game theory scenario that points to a more hopeful path, it’s important I first explain the conceptual and philosophical position I operate from as a behavior analyst.

Non-Linear Behavior Analysis As the Solution

Israel Goldiamond offered something invaluable to behavior analysis: a shift toward nonlinear thinking. Traditional behavior analysis tends to focus heavily on direct, linear relationships between antecedents, behavior, and consequences—the classic A-B-C model. While effective in many contexts, Goldiamond highlighted that real-world behavior rarely fits neatly into simple linear equations. Instead, he emphasized understanding complex contingencies and multiple interacting influences that shape our decisions. His approach challenges behavior analysts to look beyond straightforward cause-and-effect relationships, pushing us toward a deeper, more holistic analysis of human behavior.

Goldiamond's nonlinear thinking encourages us to examine behavior through broader lenses, including context, competing contingencies, and alternative ways individuals might access reinforcers. (Goldiamond & Thompson, 2004; Layng, 2009) This complexity often explains seemingly irrational behaviors—why someone might persist in self-destructive actions or why organizations consistently fail to cooperate even when cooperation would be beneficial. By examining nonlinear contingencies, Goldiamond taught us to appreciate how seemingly irrational or "defective" behaviors might actually make sense once the broader environmental and systemic factors are fully understood.

Applying Goldiamond’s nonlinear thinking today means stepping back to consider not just immediate consequences but the entire ecosystem of influences surrounding decision-making. Rather than labeling individuals or organizations as inherently cooperative or defective, we begin to ask deeper questions about the competing contingencies shaping their choices. This perspective aligns perfectly with Game Theory, giving us a richer, more nuanced understanding of human behavior—one that allows us to interpret defection not as moral failing but as a predictable response to a complicated web of contingencies. By embracing nonlinear thinking, we can design better systems, foster genuine cooperation, and more effectively navigate the complexities inherent in human interaction. But just what exactly do I mean "non-linear behavior analysis?"

To better understand what we mean by "non-linear behavior analysis," it helps to revisit the philosophical roots of our science. In their influential article Finding the Philosophic Core: A review of Stephen C. Pepper's World Hypotheses: A Study in Evidence, Hayes, Hayes, and Reese (1988) draw from Stephen Pepper’s World Hypotheses framework to clarify the philosophical assumptions underlying different scientific worldviews. Pepper proposed four primary “world hypotheses” or ways of interpreting reality: formism, mechanism, contextualism, and organicism. Each carries a unique metaphor: formism is based on similarity and classification (the "root metaphor" of form), mechanism sees the world as a machine of cause and effect (think levers and gears), organicism focuses on developmental wholes, and contextualism emphasizes the fluid, situational, and historical nature of events. Hayes and colleagues argue that behavior analysis, at its philosophic best, aligns with contextualism, particularly in how it treats behavior as inseparable from the context in which it occurs. Yet, they caution that behavior analysts are often trained with a mechanistic flavor—focusing on linear causation and isolating variables—despite our science’s roots being more consistent with the dynamic, interactional nature of contextualism. This tension explains many of the limitations practitioners face when real-world complexities defy linear logic, and it sets the stage for understanding the difference between mechanistic and contextualistic thinking.

Mechanistic vs. Contextualistic Thinking in Behavior Analysis

Mechanistic Thinking

Mechanistic interpretations are linear, focusing narrowly on direct cause-and-effect relationships. Behavior is often oversimplified into stimulus-response chains. However, this approach can leave BCBAs unprepared for more complex real-world challenges. This is often taught in the following interpretation of the three-term contingency:

While this ABC-style model is common in training and colloquial discussion, it is ultimately a mechanistic simplification that lacks explanatory power in complex, dynamic environments. The rise of the Motivating Operation (MO) rendered this linear framework increasingly outdated. Once we recognized that motivation alters both the value of a consequence and the likelihood of behavior—even in the absence of clear antecedent stimuli—the model collapsed under its own simplicity. It’s not that the ABC model is wrong per se—it’s just no longer relevant for advanced conceptual work. Yet, it persists in our language and visuals largely because of its ease of communication. It’s digestible. It's teachable. And it's usable in elevator pitches or simplified staff training. But for technical audiences, including researchers and seasoned practitioners, relying on ABC models often signals conceptual stagnation. It fails to account for the nonlinear, recursive, and contextual nature of behavior that we observe in the real world.

While the field has advanced beyond the basic three-term contingency, the commonly taught four-term contingency—Antecedent → Behavior → Consequence, mediated by the Motivating Operation—is often still framed and applied in a mechanistic way. Though it introduces a layer of complexity by acknowledging that motivation alters the value of reinforcers and the probability of behavior, it’s frequently taught as a sequential, almost formulaic chain.

This reflects a drift from our philosophical roots. B.F. Skinner himself was not a mechanist—his radical behaviorism was steeped in contextualism, emphasizing the continuous interaction between behavior and environment over time. However, as the field evolved, the underlying philosophical coherence was often lost or deemphasized in favor of procedural clarity. In doing so, we unintentionally defaulted to mechanistic metaphors that oversimplify human behavior into discrete, controllable units. The result? A model that appears sophisticated but still reflects a linear view of causation, detached from the complex, dynamic contexts that actually shape behavior.

Mechanistic views may offer clarity, but they do so at the cost of precision. They treat behavior like a machine: flip the right switch (antecedent), and you’ll get the right output (behavior), assuming the consequence is aligned. This framing encourages control over understanding and reduction over integration. It doesn’t hold up when we attempt to analyze emergent behavior, complex decision-making, or social systems influenced by countless shifting contingencies. It certainly doesn’t prepare us to program environments where cooperation must be cultivated, where reinforcers are delayed, or where contingencies interact in unpredictable ways. To meet these challenges, we need a model rooted in contextualism—one that acknowledges the full behavioral ecosystem, not just its surface mechanics. Below is a more accurate depiction of the current post-Skinnerian contextual model.

The most notable change between the two models is the importance placed on "behavior." In a linear model, behavior often distills down to a measurable action of the organism. Behavior in the contextual approach refers to any action or response made by an organism, which can be directly observed and quantified, as well as the measurable change in the environmental stimuli. This means the behavior is not the response itself but the entire operant response and all possible interactions between variables (like how MOs affect both behavior and consequences simultaneously or how postcedents affect how we describe antecedent stimuli based on their history of reinforcement as discriminative stimuli). Imagine analyzing aggressive behavior in a child. Instead of only addressing immediate antecedents and consequences, non-linear analysis considers underlying issues such as prerequisite skills deficits or broader environmental factors. Such contextual thinking results in interventions that are more effective and sustainable. Contextualistic interpretations view behavior within broader interconnected systems. This perspective aligns with Israel Goldiamond's non-linear thinking, recognizing multiple interacting antecedents, behaviors, and consequences. It allows behavior analysts to design more effective, sustainable interventions addressing multiple contingencies simultaneously.

Goldiamond's Non-Linear Thinking

Israel Goldiamond's nonlinear behavior analysis surpasses the mechanistic model, which oversimplifies behavior into linear stimulus-response relationships, by recognizing the complexity inherent in real-world contingencies. Mechanistic models assume a one-dimensional pathway, neglecting the dynamic interplay among multiple antecedents, behaviors, and consequences. Such oversimplification can render behavior analysts ineffective when faced with the multifaceted realities of human behavior, limiting intervention efficacy. In contrast, Goldiamond’s nonlinear framework considers behavior as embedded in overlapping and interacting contingencies, enabling analysts to capture the comprehensive complexity that genuinely influences behavior.

Additionally, while the post-Skinnerian contextual four-term contingency improves upon linear models by acknowledging broader contextual factors surrounding behavior, it often continues to be applied in a primarily linear and sequential fashion—antecedent, behavior, consequence, mediated by motivating operations. In practice, this tendency likely reflects a lack of coherent and consistent philosophy of science training within many behavior analytic programs, rather than a flaw in the individuals themselves. Goldiamond extends this further and programs explicitly to avoid the linear trap by conceptualizing behavior within intricate matrices of interconnected contingencies, recognizing behavior as simultaneously influenced by and influencing multiple environmental variables. This nonlinear thinking permits a richer analysis, resulting in more robust and sustainable interventions. Behavior analysts adopting Goldiamond’s nonlinear perspective are better equipped to design interventions that address systemic interactions, effectively capturing real-life behavioral complexities and thereby achieving lasting behavior change. Now, how does this relate to game theory and behavioral economics, exactly? Well, other scenarios appear to more accurately represent the real-world contingencies beyond the Prisoner's Dilemma that left us in despair and apathy.

Beyond the Prisoner's Dilemma: The Stag Hunt and Sustainable Collaboration

In the Prisoner's Dilemma, individuals face a choice between cooperation and defection, with defection often appearing as the optimal choice due to the immediate payoff. However, while defection may seem safer, cooperation usually leads to better collective outcomes. While this model highlights the tension between self-interest and mutual benefit, it doesn't always fit real-world situations, especially in business, where the consequences of cooperation or defection can vary greatly.

The Stag Hunt is a social dilemma that better represents the dynamics of cooperation in business. Unlike the Prisoner's Dilemma, where defection is the immediate, safer choice, the Stag Hunt rewards cooperation, but only if both parties trust each other. In business scenarios, collaboration often leads to greater success, but it also comes with the temptation of one party defecting, which can leave the other at a disadvantage. The Stag Hunt represents the delicate balance between the potential rewards of working together and the risks involved, making it a more fitting representation of business interactions. (Makridis, 2022)

In the Stag Hunt scenario, two hunters must decide whether to cooperate to hunt a stag or act independently to hunt a hare. Hunting a stag requires cooperation from both hunters, yielding a large payoff for both if successful. However, hunting a hare can be done individually and provides a smaller payoff. If one hunter defects and hunts the hare while the other cooperates, the defector gets a small payoff, while the cooperating hunter gets nothing. The ideal outcome, with the highest payoff, occurs when both hunters cooperate and hunt the stag together, but the risk of defection creates the potential for suboptimal results.

Applying this to organizations providing services for people with disabilities, imagine two organizations, Org A and Org B, providing therapy services for children with disabilities. If both organizations cooperate—sharing resources, training, and best practices—they can improve the overall quality of care, leading to better outcomes for children. This mutual cooperation results in the best possible payoff for both organizations and the children they serve. However, if one organization defects, acting independently to gain a competitive edge by withholding resources, the defector might see short-term benefits, but both organizations ultimately suffer, as the quality of services drops. Just like in the Stag Hunt, the best outcome for everyone is achieved through collaboration, but the risk of defection can result in lower overall success for both.

The Prisoner's Dilemma we began with earlier traditionally assumes that individuals act purely out of self-interest, leading to the conclusion that defection is the optimal choice. The payoff structure is designed so that, no matter what the other player does, defection always results in a better or at least equivalent outcome for the individual. However, this assumption of inherent irrationality—where cooperation is viewed as an irrational, risky choice—can be a flaw, especially in real-world scenarios. People don't always make decisions in a vacuum of self-interest; instead, they often factor in social context, trust, and expectations about others' behavior. This is where Makridis's (2022) dissertation adds value, as it challenges the conventional assumption of selfishness by exploring how social discounting and social projections—individuals' expectations of cooperation based on their social connections—can influence decision-making. By incorporating these social elements, Makridis provides a more nuanced and realistic understanding of how cooperation can emerge as a optimal and expected choice, even in situations where traditional game theory would predict defection.

Social Discounting and Social Projections

Social discounting refers to how individuals' willingness to allocate rewards to others changes based on social distance. Rather than measuring the absolute value of rewards, this concept examines how likely individuals are to choose rewards for others depending on their social proximity. As the social gap between the decision-maker and the recipient increases, people tend to prioritize those closer to them—such as family—while showing decreasing willingness to allocate rewards to friends, acquaintances, and strangers. In essence, social discounting reflects how social proximity influences decision-making, affecting the likelihood of choosing benefits for others.

Social projections refer to the expectations or beliefs individuals have about how others will behave in a given situation. Essentially, it's about predicting the likelihood of others cooperating based on past experiences and social trust. For example, if someone has a history of positive interactions with a person, they might expect that person to cooperate in the future. Social projections heavily influence cooperation, as people are more likely to engage in cooperative behavior if they believe others will reciprocate. A simple example is the relationship between two colleagues: if one of them breaks trust, the likelihood of future collaboration decreases because the social trust has been undermined.

Makridis's (2022) dissertation explores the relationship between social discounting and cooperative choices, particularly within the context of a balanced game, such as the Stag Hunt scenario. The study aims to investigate how social projections (i.e., beliefs about others' cooperation) influence decision-making in situations where cooperation and defection hold equal value. By focusing on this balanced game, the study challenged the traditional game theory assumption of inherent selfishness and highlighted the potential for cooperation even when defection is an option.

The methodology of the study involved collecting participants' social discount rates, social trust measures, and their cooperative choices, which were then analyzed using logistic regression models. The findings revealed that social discounting alone did not predict cooperative behavior. However, when social projections were incorporated—specifically, participants’ beliefs about others' likelihood of cooperation—social discounting became a significant predictor of cooperative decisions. These results underscore the importance of social context and expectations in shaping decision-making. The study supports the view that cooperation, often seen as irrational in traditional game theory, is instead a optimal choice influenced by the social environment and the expectations of others.

The implications of Makridis's findings for behavior analysts are significant, especially when it comes to fostering and maintaining cooperation in environments where collaboration is key to providing services. Understanding how social projections (beliefs about others' likely behavior) and social discounting (how much an individual values others based on social proximity) influence decision-making allows behavior analysts to strategically shape environments that encourage mutual cooperation. By cultivating trust and highlighting the benefits of cooperation—such as shared resources and improved outcomes—behavior analysts can help organizations work together more effectively. This could involve creating opportunities for professionals to collaborate, share best practices, and emphasize the shared goals of improving service delivery. Additionally, behavior analysts can apply social discounting principles by encouraging staff to recognize the value of investing in closer relationships with key partners and clients, reinforcing that cooperation with trusted individuals or organizations leads to better outcomes for all. Ultimately, these insights can help behavior analysts design systems that not only maintain but strengthen cooperation, leading to better services for a larger number of individuals in need. Said another way, we can program for cooperation and avoid defection, but it requires programming in constant positive feedback loops leveraging social projections to optimize social discounting.

As BCBAs delve into other fields, their personal narratives transform significantly. Initial enthusiasm about behavior analysis often evolves into a more mature recognition of its limits and the necessity of interdisciplinary knowledge. Game theory clarifies complexities in social interactions, while behavioral economics—and economics more broadly—illuminates the financial contingencies shaping daily behavior. These disciplines haven’t just broadened what I know—they’ve shifted what I’m capable of doing. In behavior analytic terms, they’ve changed the contingencies I can effectively contact and influence. It reflects a change in the alignment between my skill set, my learning history, and the resources I can now access and mobilize. Importantly, this evolution could not have occurred through a scope of competence lens alone. Scope of competence tells us what we are ethically qualified to do; Sphere of Influence tells us what we are actually positioned to affect. Without acknowledging and strategically adjusting the latter, meaningful and sustainable impact remains out of reach—regardless of how competent we are within a narrow domain.

Your Sphere of Influence: Your Key to "Saving the World with Behavior Analysis"

Behavior Analysis, although impactful, cannot alone resolve every societal challenge. Real and lasting change comes from embracing a contextual and multidisciplinary mindset, actively expanding our Sphere of Influence through intentional integration of complementary fields. Economics and game theory were provided here merely as illustrative examples reflecting my personal exploration. Your journey into "Behavior Analysis +" could and should encompass whatever areas ignite your passion and address your specific professional contexts—be it law, technology, education, healthcare, or any field that meaningfully aligns with your goals.

However, expanding your Sphere of Influence involves more than just acquiring new ways of thinking—it also requires building the skill sets, experience, and resources necessary to implement that knowledge effectively. Understanding behavior analysis in combination with economics or game theory is valuable, but without a learning history of applying those concepts in real-world settings, or without access to the financial, social, or institutional resources needed to act on that knowledge, your influence remains limited. Imagine a behavior analyst who deeply understands how to address systemic educational disparities using behavioral science and policy frameworks—but who lacks the funding, social capital, or institutional support to launch a pilot program in schools. Despite the insight and intent, real impact may be out of reach. True influence arises at the intersection of knowledge, experience, and access—where ideas can be tested, adapted, and sustained within the realities of the environments we aim to change.

Understanding and honoring the boundaries of our individual Spheres of Influence is not merely beneficial—it is essential. Recall the two foundational principles outlined earlier: first, behavior analysts have the right to strategically adjust their Sphere of Influence; second, it is our collective responsibility to ensure that perceptions of our influence accurately reflect reality. Ignoring these principles inevitably leads to wasted time, effort, and valuable resources. When we fail to realistically evaluate our skills, learning histories, and available resources, we risk applying behavioral solutions beyond our actual capabilities. This can result in frustration, ineffectiveness, and missed opportunities to effect genuine change. Many well-intentioned behavior analysts fall into this trap, attempting either to single-handedly solve massive societal issues or tragically failing to make meaningful progress due to an inaccurate assessment of their Sphere of Influence concerning the social issue at hand. However, anyone can profoundly impact their desired outcomes by realistically assessing their skillset, learning history, and resources—and by soliciting honest feedback from trusted colleagues. This enables individuals to accurately identify where and how they can meaningfully contribute, or recognize situations in which their efforts might be ineffective without first developing an entirely new set of skills, experiences, or resources necessary to expand their Sphere of Influence to match actual requirements.

Aligning "Saving the World with Behavior Analysis" with Your Real-World Impact

Social alignment provides the clearest lens for identifying meaningful patterns across your personal life, business interactions, and broader societal contexts. Your true impact emerges most effectively when your actions align realistically with the economic models and contextual realities in which you live and work. Cooperation should always serve as the default strategy—not because it’s easy or always immediately rewarding, but because it fosters long-term stability and mutual benefit. Yet defection remains a rational and often reinforced response, especially in environments shaped by scarcity, short-term incentives, or unclear contingencies. Keeping cooperation at the forefront isn't automatic; it requires ongoing intentionality, continual self-reflection, and deliberate environmental design. As the demand for behavioral solutions expands in both complexity and scale, cooperation becomes harder to sustain—and less likely to emerge organically. That’s precisely why our science must evolve from being just an analytical lens to becoming an applied necessity. Preserving the viability of cooperation in a rapidly changing world won’t happen by chance; it demands active, science-driven systems that promote, reinforce, and protect it.

This isn't just relevant to your professional mission—it’s deeply personal, too. Whether you're navigating tense political discussions, managing interpersonal conflict, or weathering personal crises, clearly defining your Sphere of Influence helps you make meaningful moves instead of burning energy on battles beyond your reach. When we internalize this mindset, we reduce stress, improve communication, and open the door to true collaboration—especially with those whose skills, perspectives, or resources complement our own. It’s not about limiting ambition; it’s about redirecting effort toward contexts where you can actually move the needle. This shift allows for more sustainable, constructive progress across the board.

Your Sphere of Influence isn’t a boundary to fear—it’s a launching pad for intentional impact. As behavior analysts, our tools are powerful, but our greatest strength lies in our ability to integrate, collaborate, and adapt. By assessing our capabilities honestly, forging interdisciplinary partnerships, and focusing our energy within our authentic sphere, we move from abstract ideals to concrete change. The world doesn’t need more isolated experts; it needs coordinated actors aligned by shared values and actionable insight. Let’s stop imagining a future where we might save the world with behavior analysis—and start building it step by cooperative step, right here, right now.

References

Goldiamond, I., & Thompson, D. (2004). The blue books: Goldiamond & Thompson’s the functional analysis of behavior, P. T. Andronis (Ed.). Cambridge, MA: Cambridge Center for Behavioral Studies. (original work published 1967).

Hayes SC, Hayes LJ, Reese HW. Finding the philosophical core: A review of Stephen C. Pepper's World Hypotheses: A Study in Evidence. J Exp Anal Behav. 1988 Jul;50(1):97-111. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1988.50-97. PMID: 16812552; PMCID: PMC1338844.

Heward WL, Critchfield TS, Reed DD, Detrich R, Kimball JW. ABA from A to Z: Behavior Science Applied to 350 Domains of Socially Significant Behavior. Perspect Behav Sci. 2022 May 17;45(2):327-359. doi: 10.1007/s40614-022-00336-z. PMID: 35719874; PMCID: PMC9163266.

Kuo, Z.-Y. (1967). The dynamics of behavior development: An epigenetic view. New York: Random House.

Layng TV. The search for an effective clinical behavior analysis: the nonlinear thinking of Israel goldiamond. Behav Anal. 2009 Spring;32(1):163-84. doi: 10.1007/BF03392181. PMID: 22478519; PMCID: PMC2686984.

Makridis, D. M. (2022). The effects of social discounting on social choices in a balanced game (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). The Chicago School of Professional Psychology

Notes:

This is a refined version of a 1h15m talk given at the 19th annual Hawaii Association for Behavior Analysis, with some adaptations. I want to thank them for creating the circumstances for me to solidify this idea and solicit feedback from colleagues. Any organizations seeking training or consultation in aligning their organization to this are welcome to reach out to me via email.

About the Author:

Ryan O’Donnell, MS, BCBA is a Board Certified Behavior Analyst (BCBA) with over 15 years of experience in the field. He has dedicated his career to helping individuals improve their lives through behavior analysis and are passionate about sharing their knowledge and expertise with others. He oversees The Behavior Academy and helps top ABA professionals create video-based content in the form of films, online courses, and in-person training events. He is committed to providing accurate, up-to-date information about the field of behavior analysis and the various career paths within it.